Lydia Powell and Akhilesh Sati, Observer Research Foundation

Continued from ORF Energy News Monitor Volume XVI, Issue 23 available at India Energy Analysis (https://indiaenergyanalysis.wordpress.com/2019/11/15/universal-access-to-electricity-in-india-is-this-an-evolutionary-or-revolutionary-outcome-part-i-1947-1975/)

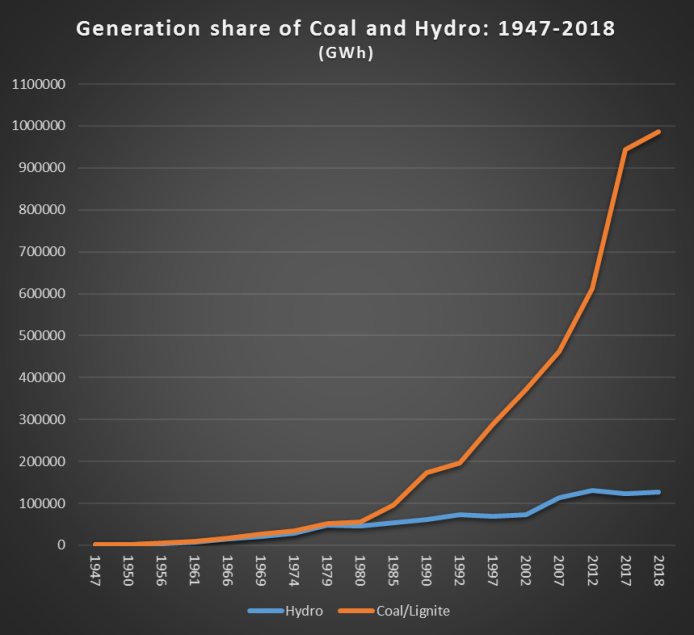

By the early 1960s, the share of villages electrified increased to about 3 percent from less than 1 percent at the time of independence. In the 1970s a substantial increase in coal based power generation that underwrote ground water pumping for the green revolution had a spill over effect of electrifying rural households (see chart).

Source: Central Electricity Authority, 2018. Growth of Electricity Sector in India from 1947 to 2018, Ministry of Power, Government of India

The push for coal based power generation was motivated primarily by the oil crises of the 1970s. The fifth five year plan (1974-79) for example called for an increase in coal based power generation to limit the use of imported oil. This was followed by a tenfold increase in the budget outlay for the coal sector to ₹10.25 bn based on the recommendations of the Fuel Policy Committee that was mandated to formulate a response strategy to global oil price crises.[1] In the following two decades, an eightfold increase in coal based generation contributed to a tenfold increase in agricultural and domestic electricity consumption. The result was that village electrification (interpreted loosely as physical connection to the grid) increased from about 7 percent in 1966 to over 26 percent in 1974.[2]

Around this time, the policy targeting electrification of rural households (not the same as electrifying villages) was revived in the form of a ‘minimum needs programme’ that aimed to provide minimum needs including electricity (free or subsidised) to rural households.[3] The rural spending programme was presented as an investment in human resource development that would increase consumption levels of the poor and consequently improve the productive efficiency of workers. It was also said to be a means to integrate social consumption programmes with economic development programmes for accelerating growth and reducing migration to towns and cities.[4] The message sought to placate industrial capital that was expected to be concerned over the substantial increase in public spending in rural areas. One of the reasons was that the heavy industry in India was among the beneficiaries of rapid electrification and subsidised access to electricity. Between 1950 and 1974, industrial energy consumption increased by over 15 percent but industrial production grew by just over 9 percent and electricity consumption per rupee of production grew by about 5 percent (indicating inefficient use of electricity).[5]

The primary concern of the federal government was electricity supply to boost agricultural and industrial production but the programme for rural electrification did have an impact on electrifying villages. By 1980 the share of electrified villages increased to about 40 percent. However household electrification was less than 20 percent.[6] In the early 80s an integrated rural energy plan that aimed to provide a basket of solutions including electricity, petroleum products, fuel-wood along with renewable energy sources to rural households was launched by the federal (central) government.[7] One of the important new approaches introduced in this plan was that the responsibility for financial support and implementation would be shared with regional (state) governments. This strategy had little or no impact on accelerating rural household electrification. In fact, growth rates of village and household electrification fell after this program was introduced and remained stagnant till the turn of the century.[8]

In the early 2000s, 86 percent of villages in India were reportedly ‘electrified’ but less than 30 percent of the households had electricity connections and there was no role for electricity in generating economic activity in the ‘electrified’ villages.[9] The tenth plan document that brought out this issue called for revisiting the definition of an ‘electrified village’ to address the divergence between village and household electrification. At that time, a village was deemed electrified if “electricity is used in the inhabited locality within the revenue boundary of the village for any purpose whatsoever”. The low bar set by the definition (that did not require the use of electricity even in a single rural household) allowed claims of dramatic increases in village electrification by successive federal governments. Even in villages where some of the households had access to electricity, the concentration of power and agency in upper caste areas meant that electrical infrastructure was often installed in these areas. Taking all the issues into account, the definition of village electrification was revised in 2004 to: ‘a village would be declared as electrified, if (1) basic infrastructure such as distribution transformer and distribution lines are provided in the inhabited locality as well as the Dalit basti hamlet where it exists (2) electricity is provided to public places like schools, panchayat (village level) office, health centres, dispensaries, community centres etc (3) The number of households electrified is at least 10 percent of the total number of households in the village.

Though the revised definition was a substantial improvement over the previous one, it did not necessarily require dependable supply of electricity to households to make the claim that a village was electrified. This was because the supply of electricity was the responsibility of the state electricity boards (SEBs) that were essentially departments of the state governments. The explanation that the supply of electricity was the responsibility of the state government and not that of the federal government was used in August 2017 by the Minister in charge of Power in response to a question raised in the parliament (Lok Sabha) over the success of the governments electricity access programme.[10]

In 2005, the flagging fortunes of household electrification programmes were revived under a new flagship federal programme: the ‘rajiv gandhi grameen vidyudikaran yojana’ (RGGVY), that aimed to provide universal access to ‘electricity to all’ in five years.[11] The programme that was tagged with the name of a political leader for the first time marked the beginning of the use of electrification programmes not only for meeting strategic or welfare goals but also for supporting political goals. Electricity was no longer just a public good that the government had the responsibility to provide and the people the constitutional right to demand; it was now a political commodity that could be exchanged for votes.

to be continued…….

Views are those of the authors

Contact: indiaenergyinsights@gmail.com

[1] Planning Commission, 1974. Fifth Five Year Plan. New Delhi: Government of India

[2] Central Electricity Authority, 2018. Growth of Electricity Sector in India from 1947 to 2018, Ministry of Power, Government of India

[3] Planning Commission, 1974. Fifth Five Year Plan. New Delhi: Government of India

[4] Ibid.

[5] Commerce Annual, 1977. Energy in Indian Economy: A Statistical Profile. Commerce Annual, 203-216.

[6] Calculated from census and planning commission data

[7] Planning Commission, 1980. Sixth Five Year Plan. New Delhi: Government of India

[8] See chart 1 in part 1 of the article available in https://www.linkedin.com/in/energy-policy-india-415338194/ or https://indiaenergyanalysis.wordpress.com/

[9] Planning Commission, 2002, Tenth Five Year Plan. New Delhi, Government of India

[10] Lok Sabha, 2017. Impact of DDUGJY. Un-starred Question No 4043 to be answered in 10.08.2017 by the Ministry of Power, Government of India available at http://164.100.24.220/loksabhaquestions/annex/12/AU4043.pdf

[11] Planning Commission, 2016, Eleventh Five Year Plan, New Delhi, Government of India

[…] from ORF Energy News Monitor Volume XVI, Issue 23 & Issue 26 [available at India Energy Analysis […]

LikeLike